But as for me, when they were troublesome to me, I was clothed with haircloth. I humbled my soul with fasting; and my prayer shall be turned into my bosom. (Psalm 34:13 DR)

There is an excellent scene near the end of the movie Becket where King Henry II has just concluded his penance for the murder of of the archibishop Becket, and speaks with his barons about how that night in council they will determine the punishment for Becket’s murderers. The barons, of course, are the murderers, and King Henry II knows they are, but he wants to be somewhat sly about it. They respond: “Sire, they are unknown.” To which he replies “Justice will seek them out, of that you can be sure.” As he exits he stops and turns to them with a knowing smirk and says: “It is time, my dear barons, for all of us to do penance.”

Penance is an often misunderstood concept as it can be construed as attempting to earn something, which is odd as it is an act of humility in which one recognizes the depths of one’s weakness and unworthiness. The penance itself is meant to lay aside the things of this world that ensnare us and tie us to its pleasures so that we may grow in deep charity with God by uniting ourselves to our Lord’s sufferings, as St. Paul describes:

And therefore we also having so great a cloud of witnesses over our head, laying aside every weight and sin which surrounds us, let us run by patience to the fight proposed to us: Looking on Jesus, the author and finisher of faith, who having joy set before him, endured the cross, despising the shame, and now sitteth on the right hand of the throne of God. (Hebrews 12:1-2 DR)

It is crucial to note that we are to look Jesus as our model who in His suffering did not suffer for sin, but rather willingly took suffering upon Himself, and thus prophetically fulfills what the Psalmist prophesies here.

The Psalmist begins by recalling the cause of his suffering and humility, which is the persecution of his enemies. Cassiodorus notes that the Psalmist is deliberating downplaying the extent of his suffering at the hands of his persecutors for rhetorical impact, using a figure called metriasmos or mediocritas. The idea behind this is to not overly emphasize the danger to which he is liable but rather to bring his humility before the Lord, as it were. That is, he is willing to suffer troublesome things as well as deeply painful things for love of God. Humility is, after all, turning one’s gaze from oneself and one’s circumstances and on to the Lord. Thus, the greatest sufferings become as nothing in comparison to the charity of God poured forth into the soul (cf. Roman 5:5), as St. Paul speaks:

But the things that were gain to me, the same I have counted loss for Christ. Furthermore I count all things to be but loss for the excellent knowledge of Jesus Christ my Lord; for whom I have suffered the loss of all things, and count them but as dung, that I may gain Christ: And may be found in him, not having my justice, which is of the law, but that which is of the faith of Christ Jesus, which is of God, justice in faith: That I may know him, and the power of his resurrection, and the fellowship of his sufferings, being made conformable to his death, if by any means I may attain to the resurrection which is from the dead. (Philippians 3:7-11 DR)

The prophecy of this Psalm in respect to our Lord may seem out of place, as we do not read of Christ being clothed with haircloth. However, the very Incarnation of our Lord is His being clothed with haircloth, for the flesh of His human nature becomes the haircloth or sackcloth with which He was humbled:

Sackcloth, haply He calls His mortal flesh. Wherefore Sackcloth? For the likeness of sinful flesh. For the Apostle says, God sent His Son in the likeness of sinful flesh, that through sin He might condemn sin in the flesh: [Romans 8:3] that is, He clothed His Own Son with sackcloth, that through sackcloth He might condemn the goats. Not that there was sin, I say not in the Word of God, but not even in that Holy Soul and Mind of a Man, which the Word and Wisdom of God had so joined to Himself as to be One Person...

With this sackcloth the Lord clothed Himself, and therefore was He not known, because He lay hid under sackcloth. When they, says He, troubled Me, I clothed Myself with sackcloth: that is, they raged, I lay hid. (St. Augustine, Expositions on the Psalms, 34, Exposition 2, 3.)

This humility in which our Lord clothed Himself in the Incarnation is the same humility with which we are to clothe ourselves, laying aside pride in imitation of our Lord Who humbled Himself even unto death (cf. Philippians 2:8).

If you’ve ever worn haircloth for any amount of time, it is not a pleasant experience. It’s not that it is excruciatingly painful or anything like that; it is, as the Psalmist says, troublesome, in that it is a scratching and itching that is constantly there, a reminder of pain that lurks just under the surface and is ready to be brought back to the front of the mind at a moment’s notice. That, after all, is the point of haircloth as a form of penance, to bring us to a remembrance of our frailty and weakness, to humble our pride and make things uncomfortable so that we do not get too engrossed in the things of this world.

Penance as a regular practice—in whatever form that takes— is meant to have this effect. One of the greatest obstacles to our growth in virtue is getting distracted by the things of this world and too comfortable with its pleasures. We can lose sight of the fact that this world is not our home, and begin to make a home here. Penance helps us to keep our eyes focused on the eternal homeland, helps us to be uncomfortable here in this world and with its ideals and mindsets. It need not be a literal hairshirt, but we are in constant need of something that scratches against our souls, so to speak, so that we remain humble in heart and focused in mind on eternal realities.

The second half of this passage expands upon the first, in that the Psalmist now speaks of fasting in addition to being clothed with haircloth. Our Lord certainly fasted as He was preparing for His temptation in the desert, and in other places encourages His disciples to fast, even speaking of how some demons can only be exorcised through prayer and fasting (cf. Matthew 17:20.) In fact, in that same passage He links prayer and fasting with belief:

Then came the disciples to Jesus secretly, and said: Why could not we cast him out?Jesus said to them: Because of your unbelief. For, amen I say to you, if you have faith as a grain of mustard seed, you shall say to this mountain, Remove from hence hither, and it shall remove; and nothing shall be impossible to you. But this kind is not cast out but by prayer and fasting. (Matthew 17:19-21 DR)

There is thus a deep inverse connection between unbelief and prayer and fasting; that is, those who do not believe will not pray and fast, because they do not think it of any efficacy, which of course demonstrates the underlying unbelief. The inverse of this is that belief includes prayer and fasting; that is, belief is not merely an intellectual apprehension and acceptance of a proposition, but is put into practice through prayer and fasting.

St Augustine perceives a mystical aspect to this well, as the hunger of our Lord is for good works:

Again, if we have understood the sackcloth, how understand we the fasting? Wished Christ to eat, when He sought fruit on the tree, [Mark 11:13] and if He had found, would He have eaten? Wished Christ to drink, when He said to the woman of Samaria, Give Me to drink? [John 4:7] when He said on the Cross, I thirst? For what hungered, for what thirsted Christ, but our good works? Because in them that crucified and persecuted Him He had found no good works, He fasted; for they rewarded barrenness to His soul. (St. Augustine, Expositions on the Psalms, 34, Exposition 2, 4.)

In His Passion our Lord was abandoned by His followers and rejected by His countrymen, these acts being a lack of good works which thus prompts our Lord’s “fasting.” That this is not a fanciful reading is proved by St. Paul, who specifically states that the good works for which our Lord hungers is the purpose of our creation and recreation in the mystical Body of Christ:

For we are his workmanship, created in Christ Jesus in good works, which God hath prepared that we should walk in them. (Ephesians 2:10 DR)

St. Augustine uses the image of fasting and eating to show how through this we are incorporated into the Body of Christ:

For what a fast was His, who found barely one thief, whom on the Cross He might taste! For the Apostles had fled, and had hidden themselves in the multitude. And even Peter, who even to the death of his Lord had promised to persevere, had now thrice denied Him, had now wept, and still lay hid in the multitude, still feared lest He should be known. Lastly, having seen Him dead, all of them despaired of their own safety and despairing He found them, after His resurrection, and when He spoke with them, found them grieving and mourning, no longer hoping anything...

In great fasting had the Lord remained, had He not refreshed them that He might feed on them. For He refreshed them, He comforted them, He confirmed them, and into His Own Body converted them. In this manner then was our Lord also in fasting. (St. Augustine, Expositions on the Psalms, 34, Exposition 2, 4.)

It is, admittedly, a rather startling image, but one that cuts to the heart of penance, which is a willing sacrifice of that which is good for that which is better. Fasting may seem like not the greatest sacrifice possible, and certainly there are others more grand, but perhaps the very banality of the act of eating is what gives it such power in the spiritual life. We eat every day, and often do so without thinking, especially in the modern world where food is so plentiful. Fasting—since in some respects it can be a small thing—thus becomes like a hairshirt, something that itches as a constant reminder of the humility which one needs to cultivate.

The point of it all is not suffering for the sake of suffering, but rather a deepening humility in imitation of our Lord, so that, as the Psalmist concludes, my prayer shall be turned into my bosom:

We are taught indeed, Brethren, that we belong to the Body of Christ, that we are members of Christ; and we are admonished in all our tribulations to consider not how we may answer our enemies, but how by praying we may propitiate God, and chiefly to pray that we be not overcome by temptation; then, that even those who persecute us may be converted to soundness and righteousness. There is no greater, no better employment in tribulation, than to retire from the noise which is without, and to go into the inner closet of the heart; there to call upon God, where none seeth thee groaning, and Him succouring ; that chamber-door to close against every invading trouble; to humble thyself in confession of sin, to magnify and praise God, both chastising and consoling: this must by every means be held firm. (St. Augustine, Expositions on the Psalms, 34, Exposition 2, 3.)

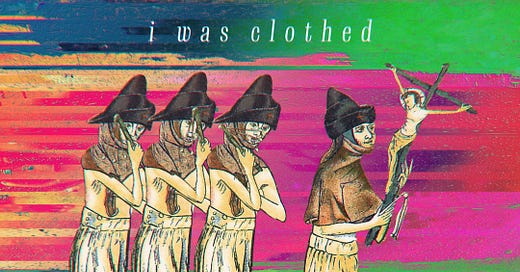

I found a great medieval miniature of some flagellants in procession and isolated them in Photoshop. In After Effects I precomped the flagellant and animated the whipping motion, which is admittedly a bit difficult to see, but that’s ok. I had isolated the feet from the body and just animated them moving back and forth to simulate walking, and then animated the position and rotation of the body slightly to help accentuate this effect.

I added in some background textures and added in some color correction and noise.

Enjoy.

But as for me, when they were troublesome to me, I was clothed with haircloth. I humbled my soul with fasting; and my prayer shall be turned into my bosom.

(Psalm 34:13 DR)

View a higher quality version of this gif here:

Share this post