Let them become as dust before the wind: and let the angel of the Lord straiten them. (Psalm 34:5 DR)

One of the great mysteries of this life is the probationary nature of it, in that there is real weight to our decisions; what we do matters. As General Maximus states in the film Gladiator: What we do in life, echoes in eternity. There is an ironic misattribution of this quote to the emperor of the film, Marcus Aurelius, who would have likely thought the opposite:

Of the life of man the duration is but a point, its substance streaming away, its perception dim, the fabric of the entire body prone to decay, and the soul a vortex, and fortune incalculable, and fame uncertain. In a word all the things of the body are as a river, and the things of the soul as a dream and a vapour; and life is a warfare and a pilgrim’s sojourn, and fame after death is only forgetfulness.

Reflect too on the life lived long ago by other men, and the life that will be lived after you, and is now being lived in barbarous countries; and how many have never even heard your name, and how many will very soon forget it, and how many who now perhaps acclaim, will very soon blame you, and that neither memory nor fame nor anything else whatsoever is worth reckoning. (Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, 2.17; 9.30)

Such is of course echoed previously in Ecclesiastes:

Vanity of vanities, said Ecclesiastes vanity of vanities, and all is vanity… All the rivers run into the sea, yet the sea doth not overflow: unto the place from whence the rivers come, they return, to flow again. All things are hard: man cannot explain them by word. The eye is not filled with seeing, neither is the ear filled with hearing… There is no remembrance of former things: nor indeed of those things which hereafter are to come, shall there be any remembrance with them that shall be in the latter end. (Ecclesiastes 1:1, 7-8, 11)

Such are the ruminations of a mind closed in on itself, that sees nothing beyond the seemingly cyclical nature of this world and the death and decay which inevitably grips everything and in which all must someday inhabit. But there is perhaps some wisdom in that a soldier in the throes of battle who consistently walks the line between life and death has a weightier perspective on his life and its meaning, than the philosopher or the sage for whom the vagaries of life are found primarily in the mind. Perhaps the inevitability of futility that seems to obtain for everything is only so because of a vision that sees only one side, or, as St. Paul says, through a glass darkly. Our moment to moment choices may hold the weight of eternity upon them without our often realizing this, which makes each moment of immense significance in a story still being written.

The Psalmist continues his discourse against his enemies, and as was seen in the previous passage, there is a probationary sense to these words of invective. He does not level imprecations absolutely, but allows for the possibility of conversion. The troubles which he wishes upon his enemies are to be from the hand of God and not his own, and thus leaves vengeance and judgment to the Lord. But it is in the midst of this chastisement that repentance and conversion can be found, and that theme—though perhaps hidden—is yet still embedded in this passage.

He begins by comparing them to dust before the wind, which brings to mind the image of his enemies being unstable and scattered. Dust driven by the wind seems to us to be helpless and blown about chaotically, which fits with the confounding and confusion following from the previous passage. Such well describes those who continue in their rebellion against the Lord:

What of others? For all are not so conquered as to be converted and believe: many continue in obstinacy, many preserve in heart the spirit of going before, and if they exert it not, yet they labour with it, and finding opportunity bring it forth. Of such, what follows? Let them be as dust before the wind. Not so are the ungodly, not so; but as the dust which the wind drives away from the face of the earth [Psalm 1:4]. The wind is temptation; the dust are the ungodly. When temptation comes, the dust is raised, it neither stands nor resists. Let them be as dust before the wind, and let the Angel of the Lord trouble them. (St. Augustine, Expositions on the Psalms, 34, 9.)

St. Augustine sees the wicked as the dust in that their obstinacy in sin causes them to offer no resistance to temptation. The shame and confounding from their sin as seen in the previous passage was the opportunity to repent, but if they reject that then they have chosen to give themselves over to depravity, and by doing so can put up no resistance to the winds of temptation which then carry them away. In this manner they fall under judgment as God gives them over to the desires of their heart (cf. Romans 1:24); He lets go of the rope; as it were, and allows them to be blown into further wickedness like dust in the wind.

Cassiodorus reads this from another more optimistic angle, in that the dust being blown by the wind still exists within this probationary framework, and is in some respect the Lord’s way of raising the sinner heavenward to repentance:

Dust is an earthy but exceedingly dry and thin substance which when the wind blows is not permitted to remain in its place, but is raised into the bright air. So the desires of sinners, once admonished by inspiration of the truth, are raised from earthly vices, and through the Lord’s help to heavenly virtues. So here the wish is expressed for wicked men that by blessed self-improvement they may obtain heavenly life. (Cassiodorus, Explanation of the Psalms, 34, 5, Ancient Christian Writers.)

There need be no contradiction or tension between these two readings, for temptation is both the means of damnation when we succumb to it, and the impelling to virtue when we overcome it, as St. James says:

My brethren, count it all joy, when you shall fall into divers temptations; Knowing that the trying of your faith worketh patience. And patience hath a perfect work; that you may be perfect and entire, failing in nothing. (James 1:2-4 DR)

We are thus either conquered by sin or conquered by virtue, and the winds of temptation which press upon us will either drive us further into sin or bear us aloft to the heavenly virtues.

This is more fully explicated in the parallelism of the second half of the passage, where the angel of the Lord is said to straiten them. This is an archaicism that isn’t used much in modern English in this form, although its sense survives in the idiom of being in dire straits. A strait is a narrow passage, often a river or waterway, that connects two larger bodies of water. As an adjective it means narrow or constricted and in this sense as a noun can figuratively mean a trying or difficult situation, particularly where one feels pressed in on all sides or with limited options. To straiten is thus to bring about this situation. In this sense then the angel of the Lord presses in upon the wicked and forces them into a certain path; he is the one who drives them forward helplessly like the wind.

This is brought out in St. Jerome’s Hebrew translation which says et angelus Domini impellat. The word impellat means to drive or push or impel, which naturally corresponds to the wind which drives them about. The Old Latin has et angelus Domini adfligens eos or et angelus Domini tribulans eos, with adfligens meaning to strike against and tribulans meaning to press or squeeze or afflict. All of these variants point to the angel of the Lord forcing the enemies of the Psalmist into a particular path that they are helpless to resist, much like the dust driven by the wind that is here one moment and gone the next:

He asks, in the third place, that they should not only be covered with confusion, and retire in confusion, but that the thing may be done quickly, and that they may be scattered in various places. Dust is carried by the wind with great force and with great speed to various places; and both force and speed are increased here by the terms used to designate them. For the term used for dust signifies the minutest, finest, lightest dust; and, therefore, the easier impelled; and it is not an ordinary wind that is to drive it, but “the Angel of the Lord, straitening them.” (St. Robert Bellarmine, A Commentary on the Book of the Psalms, 34, 5.)

However, if we take the probationary perspective of Cassiodorus, this affliction by the angel of the Lord is not necessarily for punishment, but can be for reformation. The speed and intensity of the straitening is thus meant to remove the vestiges of pride, for as the wind carries away the dust without effort, so the afflictions and temptations of this life are not something we can overcome or withstand in our own strength or force of will. If we are not overcome and conquered by grace, we will be conquered by temptation and fall into sin. In this manner the afflictions we receive from the Lord—here imaged in the angel of the Lord straitening—are an incredible mercy to lead us to humility and penance:

By angel we mean a messenger of heavenly power by whom the divine commands are carried out. So the angel afflicts the converted so that by the gift of humility they may be brought to the blessed fatherland. This affliction is a kindness, for the prayer that it may come to pass is expressed as if it were a great gift. (Cassiodorus, Explanation of the Psalms, 34, 5, Ancient Christian Writers.)

Such follows St. Paul’s words of exhortation that the Lord’s chastisement is evidence of our sonship, which provides hope even in the midst of such straitening:

And you have forgotten the consolation, which speaketh to you, as unto children, saying: My son, neglect not the discipline of the Lord; neither be thou wearied whilst thou art rebuked by him. For whom the Lord loveth, he chastiseth; and he scourgeth every son whom he receiveth. Persevere under discipline. God dealeth with you as with his sons; for what son is there, whom the father doth not correct? But if you be without chastisement, whereof all are made partakers, then are you bastards, and not sons. Moreover we have had fathers of our flesh, for instructors, and we reverenced them: shall we not much more obey the Father of spirits, and live? And they indeed for a few days, according to their own pleasure, instructed us: but he, for our profit, that we might receive his sanctification. Now all chastisement for the present indeed seemeth not to bring with it joy, but sorrow: but afterwards it will yield, to them that are exercised by it, the most peaceable fruit of justice. (Hebrews 12:5-11 DR)

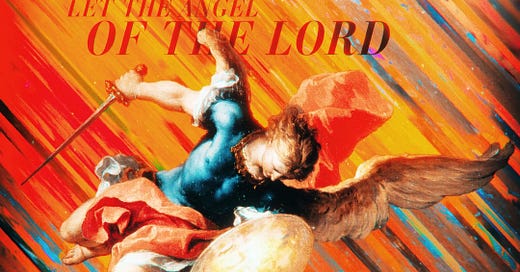

I found a great image of the archangel Michael and isolated him in Photoshop and brought the figure into After Effects. I added some shake to him by using wiggle hold on the position and rotation, bumping up the frequency.

I then brought in a colorful background texture and applied Stretch to it to create the motion streaks, making sure they were fast to give a sense of speed and force. I added a camera shake to the whole scene to give it more presence and heft.

Enjoy.

Let them become as dust before the wind: and let the angel of the Lord straiten them.

(Psalm 34:5 DR)

View a higher quality version of this gif here:

Share this post