They are corrupted, and become abominable in iniquities: there is none that doth good. (Psalm 52:2 DR)

One of the deficiencies in Stoicism that St. Thomas Aquinas critiqued was an inability to perceive evil as something more akin to a sickness or lack of health, rather than an absolute state of non-being. After all, evil is non-being, a privation of the good, but not absolutely, for otherwise an act of evil would cause the agent committing the evil (or the entity which suffers evil) to cease to exist. This has a corollary in that not all sins are of the same weight and thus do not cause privation to the same extent. He explains with far more precision:

The opinion of the Stoics, which Cicero adopts in the book on Paradoxes (Paradox. iii), was that all sins are equal: from which opinion arose the error of certain heretics, who not only hold all sins to be equal, but also maintain that all the pains of hell are equal. So far as can be gathered from the words of Cicero the Stoics arrived at their conclusion through looking at sin on the side of the privation only, in so far, to wit, as it is a departure from reason; wherefore considering simply that no privation admits of more or less, they held that all sins are equal. Yet, if we consider the matter carefully, we shall see that there are two kinds of privation. For there is a simple and pure privation, which consists, so to speak, in “being” corrupted; thus death is privation of life, and darkness is privation of light. Such like privations do not admit of more or less, because nothing remains of the opposite habit; hence a man is not less dead on the first day after his death, or on the third or fourth days, than after a year, when his corpse is already dissolved; and, in like manner, a house is no darker if the light be covered with several shades, than if it were covered by a single shade shutting out all the light. There is, however, another privation which is not simple, but retains something of the opposite habit; it consists in “becoming” corrupted rather than in “being” corrupted, like sickness which is a privation of the due commensuration of the humors, yet so that something remains of that commensuration, else the animal would cease to live: and the same applies to deformity and the like. Such privations admit of more or less on the part of what remains or the contrary habit. For it matters much in sickness or deformity, whether one departs more or less from the due commensuration of humors or members. The same applies to vices and sins: because in them the privation of the due commensuration of reason is such as not to destroy the order of reason altogether; else evil, if total, destroys itself, as stated in Ethic. iv, 5. For the substance of the act, or the affection of the agent could not remain, unless something remained of the order of reason. Therefore it matters much to the gravity of a sin whether one departs more or less from the rectitude of reason: and accordingly we must say that sins are not all equal. (St. Thomas, Summa Theologica, Prima Secundae Partis, Q. 73, A. 2.)

He elsewhere notes that the very notion of a privation from something implies that that something exists. Thus, darkness is a privation of light only when there is actually light; it does not have a being of its own, in the same way as he mentions here in the case of simple privation that one cannot be more dead than dead.

With sin, however, the non-simple privation, something of the opposite habit is retained, much like someone who is sick is lacking in a certain aspect of health, but is not sick absolutely. There is some health which still remains against which the privation of sickness is parasitic upon. In humans, as he notes, we are substantially defined by our rational nature, and even though sin wounds our faculty of reason, it does not destroy it completely, else we would cease to be rational and thus cease to exist as rational beings. The gravity of the sin exists in its departure from right reason, much like the gravity of sickness in the body is dependent on how much it departs from health. Stage 4 cancer is much more grave an illness than pneumonia, although—importantly—both can end up killing you.

The Psalmist moves from the fools who say in their hearts that there is no God to now expound upon the reasons for this. He does not adduce the more modern purported reasons that are generally predicated on intellectual objections, but instead gets to the heart of the matter—their lack of belief arises from a corruption in their souls. That is, the more they fall into sin and commit actual sin, the more they depart from reason and have their intellects darkened, which occludes the vision of the good, the true and the beautiful, all of which ultimately coalesce in God.

This corruption is not an absolute privation of good like one might find in Calvinist extravagances or the Stoics of antiquity—proving that with heresies, what is old is new again—but is rather much more akin to a sickness in the body that brings about defects and lack of health, without totally destroying the faculty of health, and thus, by analogy, of reason in respect to sin. St. Robert Bellarmine draws this out more fully:

David, therefore, says, “They are corrupt and become abominable in their ways;” that is, in their desires or affections: hence themselves are corrupted and abominable. “There is none that doeth good; no not one.” Mankind is so corrupted in desire and in iniquity, but still not so generally that all their desires and actions should be considered corrupt and unjust. For surely when an infidel, moved by compassion, has mercy on the poor or cares for their children, he doeth no evil. But nobody depending on the strength of corrupt nature alone, can perfectly and absolutely produce a good action. Hence, we see, that this passage, when properly understood, proves nothing for the heretics who abuse it, to prove that all the acts of a sinner, or of a nonregenerated, are sins. (St. Robert Bellarmine, A Commentary on the Book of the Psalms, 13, 1.)

The reason this matters is that it gets to the root of the relationship between nature, sin and grace. If man was totally depraved, as the Calvinists hold, then even the mercy of the infidel towards others would be a sin. In fact, every action, even as mundane as choosing ketchup for one’s burger rather than mustard, would be a mortal sin deserving of hell. And, to be fair, in respect to burger condiments that is probably true…

But such a view of human nature would entail that man’s reason is also totally depraved in an absolute manner, and thus—according to the Stoic analysis—more akin to a dead corpse than a sick body. But this would upend the moral constitution of God’s created order, in which acts that aren’t objectively sinful would be become sinful simply by virtue of being committed by a sinner. This would evacuate sin as an objective concept that relates to reason and would entail the eradication of the imago Dei in man since that which constitutes him as man would be eradicated by sin. St. Thomas explains this in another article in respect to whether sin diminishes nature:

Consequently its diminution may be understood in two ways: first, on the part of its root, secondly, on the part of its term. In the first way, it is not diminished by sin, because sin does not diminish nature, as stated above (Article 1). But it is diminished in the second way, in so far as an obstacle is placed against its attaining its term. Now if it were diminished in the first way, it would needs be entirely destroyed at last by the rational nature being entirely destroyed. Since, however, it is diminished on the part of the obstacle which is placed against its attaining its term, it is evident that it can be diminished indefinitely, because obstacles can be placed indefinitely, inasmuch as man can go on indefinitely adding sin to sin: and yet it cannot be destroyed entirely, because the root of this inclination always remains. (St. Thomas, Summa Theologica, Prima Secundae Partis, Q. 85, A. 2.)

All of this may seem abstract, but explains how sin can be non-being, be a privation of being, yet man still exists as a sinner. It also brings to bear the relationship of grace to the entire question, for the woundedness of sin in the soul and in the reason of man makes it impossible for him to attain to justification on his own. The diminishment of sin places those obstacles in his way that he is unable to remove, since the very diminution of sin affects the ability of reason to know the good and the ability of the will to carry it out. Man can still perform good acts (as St. Bellarmine explains), but those good acts do not attain to perfection because they arise from a diminished reason and will. They are not capable of achieving the righteousness required for justification, as the Council of Trent explains:

And whereas the Apostle saith, that man is justified by faith and freely, those words are to be understood in that sense which the perpetual consent of the Catholic Church hath held and expressed; to wit, that we are therefore said to be justified by faith, because faith is the beginning of human salvation, the foundation, and the root of all Justification; without which it is impossible to please God, and to come unto the fellowship of His sons: but we are therefore said to be justified freely, because that none of those things which precede justification-whether faith or works-merit the grace itself of justification. For, if it be a grace, it is not now by works, otherwise, as the same Apostle says, grace is no more grace. (Council of Trent, Session 6, Chapter 8.)

Grace is absolutely required as the remedy to sin for the justification of man, by which man in the Sacrament of Baptism is illuminated by the outpouring of the Holy Ghost, cleansed from Original Sin and infused with the righteousness of Christ through the outpouring of the Holy Ghost into the soul (cf. Romans 5:5).

It is thus the corruption of man’s faculties and nature which ultimately leads to being abominable in iniquities, as the Psalmist states. There is no one that doth good in the sense that St. Bellarmine noted above; in comparison to the righteousness of justification in Christ, even good acts by the faithless—which are certainly not sins—are not meritorious unto justification for the reasons explained above.

The insidious nature of corruption is that is often starts innocuously enough, but when left to fester leads to worse and worse corruption. This is why sickness is the metaphor for sin in men, for it gradually occludes his reason and inhibits his will from seeking good, and the smaller sins tends to have cumulative effect in leading to graver and graver sins. This is why the deadly sins are called deadly, not because they are in every case the worst sins, but rather because they are the gateway to graver sins. They grease the skids, as it were, of the intellect and will, making it easier to compromise, easier to let this or that slide, which—if it isn’t dealt with in Confession—leads down a road to far graver outrages. St. Augustine well describes this pattern as seen in the Book of Wisdom:

For after there had gone before the verse, The unwise man has said in his heart, There is no God; as if reasons were required why the unwise man could say this, he has subjoined, Corrupted they are, and abominable have become in their iniquities. Hear ye those corrupted men. For they have said with themselves, not rightly thinking (Wisdom 2:1): corruption begins with evil belief, thence it proceeds to depraved morals, thence to the most flagrant iniquities, these are the grades. But what with themselves said they, thinking not rightly? A small thing and with tediousness is our life (Wisdom 2:1). From this evil belief follows that which also the Apostle has spoken of, Let us eat and drink, for tomorrow we shall die (1 Corinthians 15:32). But in the former passage more diffusely luxury itself is described: Let us crown us with roses, before they be withered; in every place let us leave the tokens of our gladness (Wisdom 2:8-9). After the more diffuse description of that luxury, what follows? Let us slay the poor just man (Wisdom 2:10): this is therefore saying, He is not God. (St. Augustine, Expositions on the Psalms, 52, 3.)

The grades of sin that he mentions here as described in the Book of Wisdom are natural to our race and the common manner in which we fall into the practical atheism of living as if there is no God. It begins with wrong thinking, a turn of the intellect away from the right, and then proceeds to a refusal to receive this life as a gracious gift from God. This leads to a sort of luxuriant nihilism in which the pleasures of the world are sought for their own sake because God seems to be absent and everything meaningless. Yet sin does not stop there, for this eventually culminates in a vicious and malicious attitude towards the righteous, who one sees as standing in the way of the pleasures one desires. One becomes like a feral animal, lashing out at anything which might get between it and its food.

The irony, of course, is that in the modern world much of what the book of Wisdom describes here is seen as being sophisticated. After all, it’s only the rubes who still believe in God. They can imagine themselves to be the enlightened ones who have finally achieved the pinnacle of freedom from all the old stereotypes and prejudices and failures of our race, finally determining that it was God standing in the way the entire time. Yet the moment their ideologies are remotely threatened or even not affirmed, they lash out in spite and ad hominems and marshal the weight of whatever power or laws or whatnot they can to preserve what they deem to be their right. The last century and a half sufficiently give the lie to man’s ability to grow up or to rise above his own nature, and the sheer body counts that form the mounds upon which they stand only serve as a testament to man’s continual need for grace. Without God—and without living like there is a God—life is only vicious and vacuous. The fallout from things such as the Sexual Revolution have devastated millions, if not billions of people leaving scars in soul and body that may never heal. The promises of John Lennon’s psychopathic Imagine may seem like airy lyrics for a humanity that has come of age, but hiding behind those soft words is a cross made especially for the righteous:

Soft words they seemed but now to say: Let us crown us with roses, before they be withered. What more delicate, what more soft? Would you expect, out of this softness, Crosses, swords? Wonder not, soft are even the roots of brambles; if any one handle them, he is not pricked: but that wherewith you shall be pricked from thence has birth. Corrupted, therefore, are those men, and abominable have become in their iniquities. They say, If Son of God He is, let Him come down from the Cross. (St. Augustine, Expositions on the Psalms, 52, 3.)

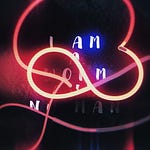

This animation was entirely procedurally generated using two plugins. Firstly I used I Ate Mushrooms which uses AI learning models to create transitions between images. I then amped up some image addition and noise to make it very abstract.

Next I applied a new one called Mad Painter which applies procedurally rendered paint strokes in the style of impressionism, with control over stroke size, brush type, and a host of other options. It’s a beast to render, but creates some really cool looks. I thought for this animation something kid of chaotic and corrupted might work well.

Enjoy.

They are corrupted, and become abominable in iniquities: there is none that doth good.

(Psalm 52:2 DR)

View a higher quality version of this gif here: