Unto the end, a canticle of a psalm of the resurrection. Shout with joy to God, all the earth, (Psalm 65:1 DR)

As with many Psalms, the inscription or title provides a key to understanding the content of the Psalm, or at least this was the opinion of many of the Church Fathers. The inscription in finem—unto the End—is especially instructive.

St. Gregory of Nyssa sees in the title Unto the End a reference to final victory culminating in a crown:

Because the inscription “For the end” is prefixed to many psalms, I think we should know something about its meaning. In this way other persons interpreting scripture may have a clear understanding of the inscription. In certain places “For the end” pertains to the phrase “For the victor,” while another psalm has “Victorious” or “For the victory.” Since victory is the end of all strife which those preparing for battle have in mind, it seems to me that the text with the brief word “end” stimulates persons training through virtue in the stadium of this life. By keeping an eye on the end, that is, victory, their labors might be lightened by the prospect of a crown. (St. Gregory of Nyssa, On the Inscriptions of the Psalms, Chapter 2, p. 32.)

St. Augustine consistently relates this End to Christ, and reads St. Paul’s words in Romans chapter 10 as the paradigmatic manner in which to not only understand this inscription, but the Psalms as a whole as pertaining to Christ:

This Psalm has on the title the inscription, For the end, a song of a Psalm of Resurrection. When ye hear for the end, whenever the Psalms are repeated, understand it for Christ: the Apostle saying, For the end of the law is Christ, for righteousness to every one believing. [Romans 10:4] In what manner therefore here Resurrection is sung, you will hear, and whose Resurrection it is, as far as Himself deigns to give and disclose. (St. Augustine, Expositions on the Psalms, 65, 1.)

And even though St. Gregory and St. Augustine have different approaches in respect to the precise referent of Unto the end, their interpretations will end up culminating in Christ, Who is the End of Whom St. Augustine speaks and the One in Whom the victory of the end is found for those who overcome and receive a crown, as St. Gregory reads.

For the end of this Psalm is specifically the Resurrection, and thus the end is understood either in light of that (in the case of the crown received) or as That in which it exists (in the case of Christ). It is—after all—the Resurrection of Christ that is the cause of our future resurrection:

But now Christ is risen from the dead, the firstfruits of them that sleep: For by a man came death, and by a man the resurrection of the dead. And as in Adam all die, so also in Christ all shall be made alive. But every one in his own order: the firstfruits Christ, then they that are of Christ, who have believed in his coming. (1 Corinthians 15:20-23 DR)

St. Augustine gives fuller commentary on this in respect to this End:

For the Resurrection we Christians know already has come to pass in our Head, and in the members it is to be. The Head of the Church is Christ, [Colossians 1:18] the members of Christ are the Church. That which has preceded in the Head, will follow in the Body. This is our hope; for this we believe, for this we endure and persevere amid so great perverseness of this world, hope comforting us, before that hope becomes reality. (St. Augustine, Expositions on the Psalms, 65, 1.)

The metaphor of Head to Body is extremely important to St. Augustine’s explanation of the Psalms, and it forms the interpretive matrix through which he reads them in their entirety. Christ as the End of which the Psalms speak is the primary object—as it were—of the Psalms. That is, He is what the Psalms are primarily about. But since the Holy Catholic Church is His mystical Body, what is said of Christ as the Head can be spoken of the Church as His Body, and thus the Psalms continually move back and forth between the Head and Body, speaking of One here and the other there. Such transitions in voice or object are thus not arbitrary but mediated through this relationship between Christ and His Body the Church.

Such can be seen in this inscription of the Resurrection, which refers principally to Christ as the One Who raised Himself from the dead as being both the Resurrection and the Life, but also to the Church whose members will share in that End of the resurrection by being united to Christ as members of His Body.

St. Augustine goes on to describe that the linking of the resurrection to the End in Christ brings about a hope in the resurrection that surpasses the shadowy notions of it that preceded the Christian hope. For among the Jews, he notes, there was a belief in the resurrection of the dead, but this belief was characterized—so he describes—by a somewhat carnal understanding, in which the state after resurrection more or less tracked with the state before, with an increase in blessedness or other such carnally-minded things:

But this hope promised to themselves the Jews had, and of their good and as it were just works they gloried much, because they had received the Law, by living according to which both here they would have carnal good things, and in the Resurrection of the dead, they hoped for such things as here they delighted in. (St. Augustine, Expositions on the Psalms, 65, 1.)

St. Augustine adduces the example from the Gospels in which the Sadducees propose to our Lord the situation of a woman who marries seven brothers in succession after each dies, wondering who will be married in the resurrection. The Sadducees of course denied the resurrection, the very denial of which proves that those who were not of the Sadducees did believe in it. However, given that the question was proposed, it seems that they had come up with a hitherto-unanswerable conundrum for those who did believe in the resurrection. For if it was an easily answered objection, they would not have brought it to Jesus as a gotcha type of question.

The reason the question seems to pose a dilemma is precisely what St. Augustine is focusing on—that such a question presupposes a somewhat carnally-minded understanding of the resurrection. The logical puzzle they propose is thus entirely grounded in such a mentality:

For this cause to the Sadducees, who denied a future Resurrection, the Jews were not able to make answer when they propounded a question which the same Sadducees propounded to the Lord. For hence we perceive that they could not solve this question, because on the Lords solving it they wondered. (St. Augustine, Expositions on the Psalms, 65, 1.)

The force of the objection, however, lies entirely in the nature of the resurrection, and thus our Lord responds by correcting the misunderstanding and misreading of the Scriptures on this point:

Without doubt the Jews would not have been hard bested, would not have failed in that question, unless in the Resurrection for themselves they had hoped for such things as they were in the habit of doing in this life. But the Lord promising equality with Angels, not any human corruption of the flesh, saith to them, Ye err, knowing not the Scriptures, neither the power of God; for in the Resurrection, neither shall the women marry, nor shall the men take wives: for neither shall they begin to die, but shall be equal with the Angels of God. He hath proved that succession is necessary in a place where decease is mourned: there because there shall be no deceased, neither should successors be looked for. For unto this He hath subjoined For they shall not begin to die. (St. Augustine, Expositions on the Psalms, 65, 1.)

It is, of course, easy for us to look back over centuries and wonder at the seemingly weird ideas that peoples of the past held, yet in this respect one might wonder if we are much different, especially in our understandings of the resurrection. It probably would not be too far of a stretch to assert that most people who hold to some idea of the resurrection or of heaven have an almost entirely carnal understanding of it, as if in heaven or the resurrection we will be mostly like ourselves now, but without the things we deem unpleasant.

However, our Lord corrects such a carnal understanding of the resurrection precisely by reference to marriage, in which something that characterizes the human race from conception to death is transcended in the resurrection, such that we are like unto the angels. It is not merely that angels do not marry, but that their existence is of a completely different quality than the one we currently lead. It is not that we will become angels—we will, after all, have bodies—but rather the likeness is meant to indicate that what we will be is more like being an angel than it is like being what we are now.

And while we certainly cannot fully intellectually grasp this, it is this resurrection and the quality thereof that is to be the ground of our hope in the midst of the trials and tribulations of this world. Such an idea probably grates against us, for there are many good things in this world—including marriage, which is itself a sacrament—which will be done away with or transcended in the resurrection. Things like marriage are—as St. Paul says—ultimately not about themselves but rather about the End of which this Psalm speaks, which is Christ.

The tinge of regret that we might feel at losing the things of this world that we love in the resurrection is itself an indication that our hearts are still attached to this world and its loves and goods. The resurrection unto eternal life is to gain all things, for it will be to be united in the Beatific Vision with God Himself, and whoever possesses God possess all things. It is rather our hearts which are too small and our desires too feeble, in that we cannot imagine fullness when we have only filled ourselves with the most banal things. As C.S. Lewis insightfully quipped:

It would seem that Our Lord finds our desires not too strong, but too weak. We are half-hearted creatures, fooling about with drink and sex and ambition when infinite joy is offered us, like an ignorant child who wants to go on making mud pies in a slum because he cannot imagine what is meant by the offer of a holiday at the sea. We are far too easily pleased. (C. S. Lewis, The Weight of Glory and other Addresses)

The Resurrection and the joy found therein is not simply in the continuance of existence or the restoration of life and the body and the joys of heaven and eternity, but rather that the resurrection is found within The End, which is Christ, Who is God over all and the One Who will be that end for all eternity. All joy and blessedness—not just some joys or certain joys or blessednesses—are found within Him and as being united to Him in His mystical Body. Any desire that we have that we think we can have apart from Christ is a mud pie in a slum, and what we really want is not God or Heaven but rather simply a nicer form of Hell, for we still wish for joy and blessedness on our terms, rather than as found in the End of all things, the One in Whom is found all blessedness forever.

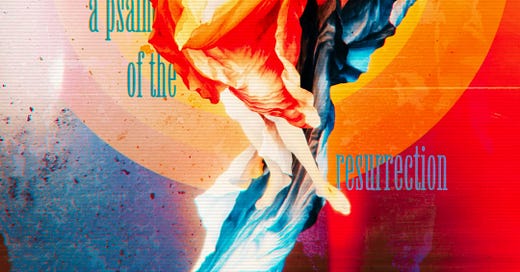

I isolated the Christ figure from Matthias Grünewald’s famous Resurrection as part of the Isenheim Altarpiece. In After Effects I rigged it up with Puppet Tools so as to able to animate the cloth.

I created a simple precomp with some scaling circles for the radiating circles in the background, and then added in some background textures and color correction.

Enjoy.

Unto the end, a canticle of a psalm of the resurrection. Shout with joy to God, all the earth,

(Psalm 65:1 DR)

View a higher quality version of this gif here:

*thanks to Richard McCambly, ocso, for the use of the PDF of St. Gregory’s On the Inscriptions on the Psalms.

Share this post